To understand The 400 Blows, it’s necessary to start in 1932, twenty-seven years before the film premiered. On February 6th of that year, a young Frenchwoman named Janine de Monferrand gave birth to a son whom she named François. Neither Monferrand nor her family wished to deal with the stigma of unwed motherhood, so she placed the baby in the care of a wet nurse. Upon her marriage to Roland Truffaut in November 1933, her new husband gave François his surname, but the child remained with the wet nurse until almost age three, when his maternal grandmother realized that he was languishing and decided to take him in. He stayed with her until her death in 1942, at which point he went to live with his mother and stepfather for the first time. The transition was not a smooth one. François Truffaut felt unwanted and unloved. He drifted into petty crime, was sent to the Paris Observation Center for Minors, joined the army, went AWOL, spent time in military prison. It all might have ended very badly indeed if it hadn’t been for one saving grace: his love of movies.

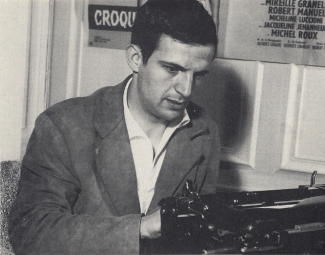

With help from André Bazin, his mentor and father figure, Truffaut became a film critic for such publications as Arts-Lettres-Spectacles and Cahiers du cinéma, a magazine co-founded by Bazin. He soon gained a reputation for ruthlessness, especially after his article “Une certaine tendance du cinéma français” (“A Certain Tendency of French Cinema”) appeared in Cahiers in January 1954. In this piece, he attacked the French film industry’s so-called “Tradition of Quality,” which he found false and overly literary, and praised “auteurs” like Jean Renoir, Robert Bresson and Jacques Tati, whose work he considered more cinematic and who often wrote their own dialogue and stories. “I would try to make people want to see certain films,” he said in a 1965 interview on the French television program Cinéastes de notre temps. “I was really trying to turn them away from other films.”

Like a number of his Cahiers colleagues — most notably Jean-Luc Godard, Éric Rohmer, Jacques Rivette and Claude Chabrol — Truffaut soon moved from theory to practice. In the aforementioned interview, he said, “I think that the plan — I don’t know if there was actually a plan — but as far as I’m concerned, it never occurred to me, if I were to make films, to revolutionize cinema or express myself differently than previous filmmakers. I always thought that the cinema was fine. It just lacked sincerity. I’d do the same thing, but better.” In 1954 he wrote and directed an eight-minute short called Une Visite but was dissatisfied with the result. After spending two years as Roberto Rossellini’s assistant, he decided to try his hand at directing again. His 1957 short Les Mistons, which he adapted from a story by Maurice Pons, is about a group of preteen boys who harass an older girl and her boyfriend as a means of dealing with their feelings for her. Not only did it attract positive attention for the fledgling filmmaker — he was named Best Director at the Brussels World Film Festival — but it helped him realize that he enjoyed working with children.

Truffaut made one more short (Une Histoire d’eau, a collaboration with Godard) before embarking on his first feature. Abandoning a project called Temps chaud, he planned to make an episodic film about childhood. He would eventually do something along those lines with 1976’s L’Argent de poche, but in 1958 he scrapped much of that project in order to expand one of the segments. La Fugue d’Antoine was the story of a boy who tells a lie at school and is afraid to go home. Along with writer Marcel Moussy, he turned the short sketch into a treatise on adolescence, a portrait of a troubled youth — one whose circumstances were very much like his own. In fact, Truffaut intended to set the film during the Occupation, the era of his formative years, but due to the expense that a period piece would entail, he decided to transpose it to the present. He named it Les Quatre Cents Coups (The 400 Blows) after a French phrase, as he would later explain in his introduction to the Antoine Doinel screenplays: “During [adolescence], a simple disturbance, or upset, can spark off a revolt and this crisis is precisely described as adolescent rebellion: the world is unjust, one must cope with it anyway, and one way to cope is to raise hell. In France this is known as ‘faire les quatre cents coups.'”

The next step was to find someone to play the main character, Antoine. About sixty boys responded to an advertisement that Truffaut placed in France-Soir in September 1958, and one in particular stood out.

Jean-Pierre Léaud was fourteen years old, the son of actress Jacqueline Pierreux and writer/assistant director Pierre Léaud. Although he had had a small part in the 1958 film La Tour, prends garde! (on which his father had worked), he was primarily a student, and not a model one. His parents had sent him away to boarding school at age six, and by the time he auditioned for The 400 Blows he had been expelled from quite a few such institutions. (The number of schools Léaud had attended varies from source to source, including interviews with the actor himself, but it’s usually somewhere around a dozen.) In a letter of non-recommendation, his current headmaster told Truffaut that the boy exhibited “indifference, arrogance, permanent defiance, lack of discipline in all its forms” and was increasingly becoming “an emotionally disturbed case.” This did not deter the director, who was impressed by Léaud’s energy and his desire to win the part. He debated whether to cast him as Antoine or as Antoine’s best friend, René, but after conducting additional screen tests he gave Léaud the lead. The other boys who had auditioned were employed as Antoine’s classmates.

Filming ran from November 1958 to January 1959. On November 11th, just one day after the shoot commenced, André Bazin died of leukemia at age forty. Truffaut dedicated The 400 Blows to his memory.

The film follows Antoine Doinel, a boy of twelve or thirteen who lives in Paris with his mother, Gilberte (Claire Maurier), and his stepfather, Julien (Albert Rémy) — ostensibly his father. From the start, it’s clear that they’re not the most doting parents in the world. Julien jokes around with Antoine, but he also asks his wife, “Speaking of kids, what’ll we do with this one for the summer?” right in front of him. “Summer camp ain’t for poodles,” she replies. Gilberte constantly gives the impression that Antoine is an annoyance, an impediment; she even has to step over his bed when she comes home late. During an argument with Julien, which Antoine overhears, she threatens to send her son away to the Jesuits or the army orphans. “At least I’d have some peace and quiet!” — this in spite of the fact that Antoine generally keeps to himself in her presence. He’s a secretive boy, whether he’s examining his mother’s belongings while she’s out, building a clandestine shrine to Honoré de Balzac or simply lying and stealing, and part of the reason may be because he doesn’t want to draw too much attention to himself and risk irritating her. Only after he catches her kissing a strange man does she become affectionate toward him and try to win his confidence. “You and I can share some little secrets,” she says before resorting to outright bribery in order to keep him from saying anything. He goes along with it, and doesn’t even acknowledge what happened, but he rolls his eyes. (Julien, for the record, at least suspects that Gilberte is unfaithful to him, and he implies as much more than once.)

School is little better than home. Antoine is always getting in trouble, sometimes through no fault of his own (like when the students are passing around a pinup and he’s the one who gets caught with it), sometimes because of his tendency to either lie or run away whenever he gets into a difficult situation. It does have one slight advantage, though: his best friend, René Bigey (Patrick Auffay). He’s the only person in whom Antoine can confide, somebody who’s always ready to help and advise him, for better or for worse. Like Antoine, René is prone to dishonesty, and he seems to have no qualms about any of it: pilfering his alcoholic mother’s money (“an advance on my inheritance”), skipping school, forging excuse notes. On the plus side, he’s intensely loyal, and he gives Antoine a place to stay whenever he can’t face going home to his parents. Neither one of them appears to have any other close friends, so René relies on Antoine almost as much as Antoine relies on him. When the two boys decide to steal and sell a typewriter, however, Antoine finds himself in more dire straits than ever before, and he has to deal with the consequences on his own.

Much of The 400 Blows was drawn directly from Truffaut’s early life. The family situation is almost identical, right down to the fact that Antoine was sent to a wet nurse and then to his grandmother before living with his parents. Like Truffaut, he was born out of wedlock and only learned the truth by accident, when he overheard his mother and grandmother fighting about it; Truffaut found out at age twelve upon discovering that there was no mention of his birth in his stepfather’s 1932 almanac, and the family record book soon confirmed that Roland Truffaut was not his real father. His mother shared Gilberte’s desire for peace and quiet: “My mother couldn’t bear noise and asked me to remain without moving, without speaking, for hours and hours,” he said. Truffaut also stole and sold a typewriter from his stepfather’s office when he was sixteen, but instead of being caught like Antoine, he got away with it, at least temporarily. After being confronted by his stepfather, he confessed to several thefts, and his stepfather paid off his debts on the condition that he find a steady job and stop spending so much money on his film club. The crime that landed him in the Paris Observation Center for Minors a few months later was his failure to pay MGM five thousand francs for a print of King Vidor’s The Citadel, which he and his friend Robert Lachenay had rented for a film club screening. Lachenay was the real-life René, and he worked on The 400 Blows as an assistant unit manager.

Comparatively minor aspects of the film were just as autobiographical. In the 1965 Cinéastes de notre temps interview, Truffaut said, “I played hooky quite a bit, so all these problems with notes, signatures, fake excuses, signed report cards, I knew them by heart, of course.” He then talked about hiding his school bag in doorways while he went to the movies, as Antoine and René do, “because two or three theaters in Paris opened at 10:00 a.m. The clientele was made up almost exclusively of school children. You couldn’t go with your school bag. It would look suspicious.”

When Antoine has to give his teacher an excuse for his absence the previous day, he blurts out that his mother died; Truffaut once did the same thing. (On another occasion, during the war, he claimed that his stepfather had been arrested by the Germans.) Antoine plagiarizes Balzac for an essay; so did Truffaut. Antoine sees his mother kissing her lover on the street; so did Truffaut. Suzanne Schiffman, Truffaut’s friend turned script supervisor turned assistant director and co-writer — in short, his right-hand woman — recalled that the teenage future filmmaker would steal milk bottles as they walked home from the Cinémathèque Française; Antoine reenacts this while wandering the city one night after running away. Even the humorous scene with the gym teacher, who takes the students for a jog along the street and doesn’t notice that the group quickly dwindles to only a few boys, came from Truffaut’s memories.

Naturally, Janine and Roland Truffaut recognized themselves in Gilberte and Julien Doinel, and they were less than pleased. At that time, they had little contact with their son, who was going out of his way to avoid them — they only found out about the January 1959 birth of his first child, Laura, two months later, when they read about it in the press — and the film precipitated a total estrangement that would last for three years. There’s a scene near the end that may have been based on the past but also seems to anticipate Truffaut’s parents’ reaction. Gilberte visits Antoine at the observation center, where they have the following exchange:

Gilberte: Your letter to your father hurt him very much. You were naive to think he wouldn’t show it to me. In spite of appearances, we’re a devoted couple, and it wasn’t smart to remind him of some unhappy days I went through. Thanks to him, you have a name. We were ready to take you back, but the neighbors’ gossip put an end to that. You must have told everyone in the neighborhood!

Antoine: I never said a word, Mother.

Gilberte: But I’m used to it. I’ve been criticized by imbeciles all my life. Anyway, that’s all I had to tell you. And don’t go crying to your father. He said to let you know he’s washed his hands of you completely.

Indeed, Roland Truffaut was outraged that his stepson had dredged up the family’s past in such a public manner, and he wrote him a furious letter in May of 1959, a few weeks after the film’s premiere; he referred to Truffaut as “a glorious and disinterested ‘child martyr'” and signed it “Your father (merely legal).” Truffaut responded with a letter of his own. Although he expressed regret that the press had printed untrue or distorted information, he said, “I haven’t the slightest regret about having made this film. I knew I would hurt you, but I don’t care, for since Bazin’s death I have no parents. I would have shot a truly horrifying film had I depicted what my life was like on the rue de Navarin between 1943 and 1948, and my relationship with Mom and you.” After running through a litany of neglect and emotional pain, he wrote, “The film, which is infinitely less violent than this letter, will certainly hurt you, and it’s not true that I don’t care. I thought of you constantly while making it and I improvised a few scenes to avoid being unfair, convince you of my good faith and show you, partially, what I think was the truth.”

To make amends, Truffaut started to downplay the film’s real-life elements, going so far as to publish an article in Arts called “I Did Not Write My Autobiography in The 400 Blows.” In it, he claimed that Antoine’s parents “absolutely do not resemble mine, who were excellent” and suggested that Marcel Moussy’s television work played a larger role in shaping the characters. (Elsewhere, his account of Moussy’s influence was quite different: “If I had been alone, I would have been inclined to portray my parents in a very caricatured manner, to create a violent, subjective satire, and Moussy helped me make these people more human, closer to the norm.”) This failed to conciliate Roland and Janine, so Truffaut cut off all contact with them.

In a 1969 interview with The New York Times, Truffaut claimed that he had expected viewers to be more sympathetic to the parents: “I felt the public was too severe with the parents and too indulgent with Antoine. Because I had wanted to show that the parents were totally at a loss with this unpredictable kid, who does everything in hiding. But the way it came out, the child was adorable.” A decade after the fact, this may have been revisionism on his part, but as he told his stepfather, he did include scenes in which Gilberte and Julien are portrayed sympathetically. At one point, for example, Julien defends Gilberte to Antoine: “I know what you’re thinking: She’s been hard on you lately. But she’s under a lot of pressure. Put yourself in her place. Keeping house and working part-time, and this place as cramped as it is.” In another scene, the three Doinels go to the movies together, a happy and harmonious family to all appearances. When Antoine takes the garbage downstairs that night, he has a subtle smile on his face that speaks volumes.

Despite its heavy themes, there are numerous lighthearted moments in The 400 Blows. The scene in which Antoine and René take a little girl to a puppet show is particularly lovely. (It’s not clear who she is — perhaps a cousin or some other acquaintance of René’s.) While the two boys sit in the back of the room, plotting their typewriter theft, the camera’s focus is on the young children in the audience, and their genuine reactions are a delight to watch. Even Antoine and René seem amused by the show, in spite of their ever-growing cynicism. They may have lost much of their innocence, but they aren’t so far removed from childhood after all.

In another memorable scene, Antoine gets on a spinning carnival ride called a rotor. (Truffaut makes a cameo as one of the other riders, and he walks past the camera as he exits.) School and home are both repressive environments for him, but here he’s liberated and joyous, completely open and unrestrained (although, as he’s playing hooky, this carefree state is short-lived). Throughout the movie, he goes back and forth between varying degrees and forms of freedom and confinement. Freedom isn’t always positive, however. When he runs away from home, René lets him sleep at his uncle’s printing plant, but he has to leave before the night is over because the employees arrive. He then wanders the streets until it’s time for school, terribly alone, in one of the film’s saddest sequences. Except at the beginning, when Antoine encounters a woman (Jeanne Moreau) whose dog has escaped, there’s no dialogue; Léaud’s performance, Jean Constantin’s score and the relatively empty city — incongruously decorated for Christmas — are more than sufficient to convey Antoine’s sense of isolation. It parallels a scene later on: Antoine makes another nocturnal journey through Paris, but this time he’s in a police van. The film’s ending, too, is a potent mixture of liberation and loneliness. (A major influence on the iconic final shot was Ingmar Bergman’s 1953 film Summer with Monika; perhaps as a nod to this debt, Antoine and René steal a still of actress Harriet Andersson as Monika while leaving a movie theater. Notably, in Truffaut’s 1973 film Day for Night, the character Ferrand — a director, played by the director himself — has a recurring dream about stealing Citizen Kane stills when he was a child.)

Freedom and confinement are also fundamental to one of the most famous scenes in The 400 Blows: Antoine’s interview with the psychologist. Despite the fact that Antoine is in a juvenile detention center and this session is mandatory, he appears to be completely honest as he answers her questions, telling her about his past misdeeds and his difficult relationship with his mother. Truffaut took special pains with this scene, which he saved until the second-to-last day of filming. In his book of Antoine Doinel screenplays, he wrote that “one of my primary concerns was to achieve a maximum of truth and it seemed to me that Jean-Pierre Léaud was not as natural and genuine as he had been in the 16-millimeter tests we had made prior to the shooting.” To achieve this, he had a sound camera and microphone set up (the rest of the movie was shot without direct sound) and dismissed the crew, then sat down across the table from Léaud and began asking questions that the actor had not been given beforehand. A woman’s voice is dubbed over Truffaut’s in the completed film, but the psychologist is never seen. At the Cannes Film Festival in May of 1959, Léaud described how the scene was shot:

I wasn’t given the words. Truffaut had told me about it a month in advance. He said this scene had to be the best scene of the film. He told me a month in advance so I could get used to the idea. The day we shot it, he asked me questions, and I was to answer however I wanted. In the beginning it wasn’t working, so he gave me some ideas that I would then flesh out to say what I had to say.

One of Truffaut’s suggestions must have been the reference to Antoine’s early years with the wet nurse and his grandmother, but he said that Léaud “was so spontaneous in his replies that some of them were based upon his own life,” including the other grandmother story that Antoine tells.

Léaud had a significant impact on the way the film turned out, and not just because of his performance. “At the time, I was extroverted, boisterous, and François, in contrast, was reserved, very introverted,” he said in a 2001 interview with Libération. “The character was adapted to my dynamism. I think that was what he liked in me, that energy. He noticed it immediately during casting. I gave him life. He took it to make a character.” Truffaut often said the same thing. “I was thinking of a more introverted child,” he told The New York Times, “and I kept adapting the screenplay to suit him.” Carole Le Berre offers an example in François Truffaut at Work:

In the first screenplay with dialogue, it is René who rides in the rotor at the carnival while Antoine watches. Truffaut then inverted their respective places and gradually swapped around characteristics between the two friends. Initially he had imagined that Antoine would be submissive and anxious, as Truffaut was himself, in contrast to a version of René who is more enterprising, like Truffaut’s childhood friend Robert Lachenay.

In his commentary on The 400 Blows, Lachenay remarks that even something as trivial as the casual way Antoine walks across the classroom after being punished is much closer to Léaud — or Lachenay himself — than Truffaut, who was “rather shy” and “more likely to hug the walls.” Like René, Lachenay was fairly wealthy, and this gave him a confidence that Truffaut lacked, though he was neglected by his parents as well.

Truffaut described the fourteen-year-old Léaud as a “valuable collaborator” who “instinctively found the right gestures, his corrections imparted to the dialogue the ring of truth and I encouraged him to use the words of his own vocabulary.” Although he acknowledged major differences between them — whereas the young Truffaut was sneaky and given to lying, Léaud “seeks to hurt, shock and wants it to be known,” as Truffaut said in Paris-Journal in 1959 — they also had much in common, including “a certain suffering with regard to the family.” At the beginning of the shoot, Léaud lived with his parents — his current school was over a hundred miles from Paris — but it proved to be such a volatile situation that Truffaut took him in. From that point on, he became a father figure and big brother to Léaud, just as Bazin had been to him. “He was very humane and generous,” Léaud later said, “undoubtedly because cinema had saved him too.” Truffaut noted that upon seeing the completed version of The 400 Blows for the first time, “Jean-Pierre, who had laughed his way through the shooting, burst into tears: behind this autobiographical chronicle of mine, he recognized the story of his own life.” The lines separating director, actor and character had already begun to blur.

The 400 Blows premiered at the Cannes Film Festival on May 4, 1959. Truffaut had frequently criticized the event, which he accused of being too closely tied to the established French film industry, too concerned with money. “Movies are for the people who make them, who love them, who go to see them, and not for those who profit by them,” he wrote in 1956. As a result of this and similar articles, he was refused accreditation as a journalist in 1958, which prompted him to change his byline in Arts to “François Truffaut, the only French critic not invited to the Cannes Festival.” His reception in 1959 was quite the opposite: The 400 Blows was a triumph, Truffaut won the award for Best Director and he and Léaud became the stars of the festival.

Jacques Doniol-Valcroze, a colleague at Cahiers du cinéma, called the movie “a sudden missile exploding right in the enemy camp.” It brought international attention to the nascent French New Wave, a largely disorganized group of young filmmakers working outside, and against, the studio system, and strongly influenced by Truffaut’s writing. He was at the forefront of the movement, and in many ways, Antoine Doinel — via Jean-Pierre Léaud — was its face.

Gallery

Sources

Andriotakis, Pamela. “Jean-Pierre Leaud, Truffaut’s Favorite Star, May Finally Outgrow Life & Love on the Run.” People 25 June 1979.

Carr, Jay. “Jean-Pierre Leaud Going It Alone with Loss of Father-Protector.” Chicago Tribune 28 April 1985.

De Baecque, Antoine, and Serge Toubiana. Truffaut: A Biography. Trans. Catherine Temerson. New York: Knopf, 1999.

De Gramont, Sanche. “Life Style of Homo Cinematicus.” New York Times 15 June 1969.

“François Truffaut ou l’esprit critique.” Cinéastes de notre temps. 2 December 1965.

Ingram, Robert. François Truffaut: The Complete Films. Cologne: Taschen, 2013.

Lachenay, Robert. Audio commentary. The 400 Blows. Criterion, 2003.

Léaud, Jean-Pierre. Interview. Reflets de Cannes. 1959.

Le Berre, Carole. François Truffaut at Work. Trans. Bill Krohn. London: Phaidon, 2005.

Peron, Didier, and Antoine de Baecque. “Leaud, retour à Doinel.” Libération 31 August 2001.

Le Roman de François Truffaut. Paris: Editions de l’Etoile, 1985.

Ross, Walter S. “The Actor the French Dig the Most.” New York Times 28 June 1970.

Truffaut, François. The Adventures of Antoine Doinel. Trans. Helen G. Scott. New York: Simon and Schuster, 1971.

Truffaut, François. “Une certaine tendance du cinéma français.” Cahiers du cinéma January 1954.

Truffaut par Truffaut. La Cinémathèque française, 2014.

The Adventures of Antoine Doinel

The 400 Blows (1959) | Antoine and Colette (1962) | Stolen Kisses (1968)

Bed and Board (1970) | Love on the Run (1979)

This post is part of the Criterion Blogathon, hosted by Criterion Blues, Speakeasy and Silver Screenings. Click the banner above to see all the other great posts.

This is an amazing start to your series – and an amazing start to the Criterion blogathon. Thank you for sharing all your research.

Jean-Pierre Léaud’s audition film is fascinating. You can see the boy’s natural charisma, and can sense he has the ability to “carry” a film.

I also found your post quite moving when describing Truffaut’s childhood, the estrangement from his parents, and the death of his mentor/father-figure. But I think the most touching part of all was learning that Truffaut took Léaud in and, in turn, became his mentor.

Your post proves that there is sometimes a very rich history behind the films we see, and I’m looking forward to your next instalments. 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks so much! I knew the basics behind the film going into this, but as I delved into some of my sources — especially the biography, which was invaluable — I was amazed by how much was taken directly from Truffaut’s life. It’s interesting, too, to see how his relationship with his parents affects the whole series, right up to the last movie, and I’ll cover that when I get there.

Yes, Léaud’s audition is fascinating. The Criterion edition also includes another audition clip in which he’s talking to Patrick Auffay, the actor who plays René, and it’s fascinating to see how much more dominant Léaud’s personality is, especially in light of the way Truffaut envisioned their characters. (There’s also a weirdly entertaining audition by Richard Kanayan, whom Truffaut would later cast as Fido in Shoot the Piano Player.) It’s also fascinating to see how much Truffaut shaped his life, and how their relationship paralleled Truffaut’s relationship with Bazin.

I hope to have the second part ready tomorrow. Thanks for reading!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Great post about a wonderful film. It really is fascinating how much of himself Truffaut put into the Antoine Doinel films, think it is part of their charm. Look forward very much to reading the second part.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you! Yes, the autobiographical elements really add another layer to the films — even the later ones, which are further from Truffaut’s life and generally lighter in tone.

LikeLike

I’m so impressed by the work you put into this, it was a joy to read and learn these things about the background, production and personal elements of a great film. Like Ruth said, already off to a fine start to the blogathon and your series, looking forward to the rest, thanks so much for the contribution!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you! Yes, as great as the film is on its own, knowing the background really enriches the whole experience.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I know I’m late to the party when you started so early, but you have set the bar high. I’ve read the first two, and soon will tackle the third. Great stuff so far!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you! I really appreciate it, and I’ve had a lot of fun writing these. I know the films pretty well, so I’ve enjoyed putting my thoughts in order and exploring the behind-the-scenes aspects in depth. Plus, I’ve managed to accumulate quite a few Truffaut books over the past year or two, and it’s nice to be able to put them to use. Thanks for hosting the blogathon!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Such a lovely film, and a lovely review. Appreciated the background on Truffaut’s own boyhood.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you! Yes, knowing the background really enhances the movie.

LikeLike