Is it possible to discuss Two English Girls without bringing up Jules and Jim? François Truffaut’s 1971 film seems to live in the shadow of its better-known predecessor, shot ten years earlier, and not without reason. Both movies are based on semi-autobiographical novels by Henri-Pierre Roché; both were made by several of the same people, including Truffaut, screenwriter Jean Gruault and composer Georges Delerue; both feature narration throughout; and both focus on complex love triangles that shift and evolve over the course of quite a few years. In fact, a quick glance at a written summary of Two English Girls might suggest little more than a gender-flipped version of Jules and Jim, with its triangle comprising two women and a man instead of two men and a woman. However, in watching the film, it becomes clear almost immediately that Truffaut’s aims were drastically different this time around.

Jules and Jim, set in the early decades of the twentieth century, concerns the eponymous best friends (Oskar Werner and Henri Serre, respectively) and their mutual love for a headstrong, intriguing, volatile woman named Catherine (Jeanne Moreau). She marries Jules and has a daughter, and later embarks on a passionate affair with Jim, yet throughout the many fluctuations of these romantic relationships, the central trio manages to remain largely on good terms — even living together in happiness and harmony for a time. “Because of that, the whole film bathes in an atmosphere that is familial and gentle — and that’s what pleased me: ‘to make a subversive film that was completely gentle,’ without assaulting the audience, but, to the contrary, enveloping it in tenderness, forcing it to accept on the screen situations that it would have condemned in real life,” Truffaut said in 1975.

Still, the film is not without its harsher moments, though these tend to be offset by its general briskness and air of detachment. When Truffaut appeared on the television program Bibliothèque de poche in 1966, it was suggested to him that certain scenes might have been made more dramatic instead of being handled “with a sort of cheerful half smile,” as the interviewer put it. “I don’t think that would serve Roché well,” Truffaut replied. “He wrote this at a distance of fifty years from events that must have been highly dramatic at the time: this woman who leaves him, waves a revolver around, leaps out the window, throws the key away. All this must have been painful to live through, yet fifty years later it enchants him. I don’t think he’s lying to himself. It’s the distance in time. The film needs that same distance. And we made this film deliberately not wanting people to take it too literally or believe it too strongly.” He termed it “an old man’s film,” though he himself was only twenty-nine when he directed it.

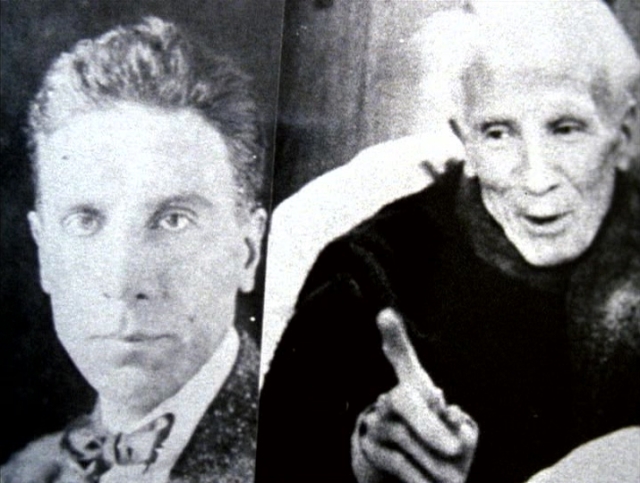

Roché, born in 1879, was an art collector, translator and journalist who “remained a dilettante all his life, for he always preferred other’s work to his own” (to quote Truffaut), and who was noteworthy for introducing Gertrude Stein and her brother Leo to Pablo Picasso in 1905. By the time he wrote Jules and Jim, his first novel, he was in his seventies. (Jules and Catherine — Kathe in the book — were based on a couple named Franz and Helen Hessel; Jim was Roché himself.) In 1955, two years after its publication, then-film critic Truffaut happened upon Jules and Jim in a secondhand bookstore. Attracted by its musical title and the fact that it was the debut novel of a septuagenarian, he fell in love with it “from the very first lines.” When he mentioned his admiration for the still-obscure tale in a review of Edgar G. Ulmer’s The Naked Dawn, Roché wrote him a letter of thanks and promised to send him a copy of his second novel, Two English Girls (originally Deux anglaises et le continent). The two struck up a correspondence and also met in person several times. As early as 1956, Truffaut expressed a desire to turn Jules and Jim into a film, an idea that pleased Roché, although he wouldn’t live to see it come to fruition — he died in 1959, just shy of his eightieth birthday.

In adapting Jules and Jim, Truffaut and Jean Gruault also drew elements from Two English Girls; for example, the brief opening voiceover, spoken by Jeanne Moreau over a black screen (“You said, ‘I love you.’ I said, ‘Wait.’ I was about to say, ‘Take me.’ You said, ‘Go away.'”), comes from Two English Girls, as does the minor character Thérèse. Eventually, the director decided to turn Roché’s second novel into a film in its own right, but with a very different approach. “Jules and Jim was filmed from a distance, both in space and time, and the painful shocks were blunted,” he told Le Monde in a November 1971 interview. “For Two English Girls, I wanted people to feel the emotions of the characters along with them and, if possible, for one to feel them physically.” It fits the source: whereas Jules and Jim is narrated in a third person, detached style (“telegraphic,” Truffaut called it), Two English Girls is made up of letters and diaries, with the characters relating their intimate thoughts, feelings and experiences more or less as they happen.

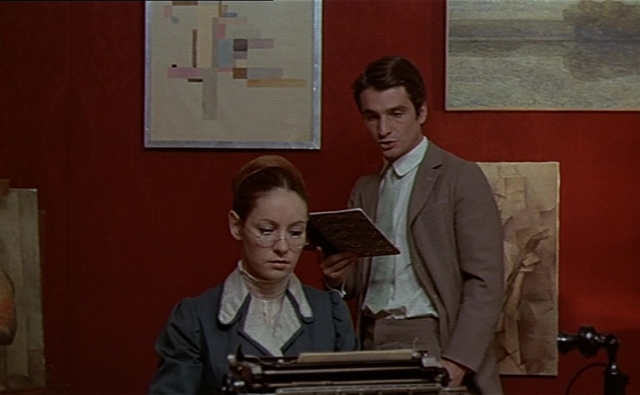

Here, Roché’s alter ego is Claude Roc (Jean-Pierre Léaud), a well-to-do young man about twenty years old at the beginning of the film. Through his mother (Marie Mansart), he becomes acquainted with Anne Brown (Kika Markham), an Englishwoman his own age and the daughter of one of his mother’s childhood friends (Sylvia Marriott). Anne is an aspiring sculptor, and during her stay in Paris, she and Claude bond over their mutual interest in art. She invites him to visit her family in Wales; he accepts, and it’s there that he meets her sister, Muriel (Stacey Tendeter). The three young people become great friends, “an inseparable trio,” but it’s not long before romantic love upsets their idyll, as Claude and Muriel develop feelings for each other and hope to marry (though Muriel resists at first, insisting that she loves him as a brother only). Their plans hit an obstacle, however — not Anne, as might be expected, for she intended them for each other from the start, but their mothers, Claude’s in particular. (A widow since before he was born, she clearly wants to keep him to herself, argue though she might that she’s concerned about his health.) It’s decided that the two should separate for a year and may marry afterwards if they still wish to do so. Muriel remains devoted, her growing love for him becoming an obsession; Claude, in contrast, soon breaks the engagement, preferring to focus on his work and enjoy the company of other women — including Anne.

Just as they had borrowed material from the novel Two English Girls for Jules and Jim, Truffaut and Gruault incorporated elements from the novel Jules and Jim into Two English Girls: Claude’s story about a suicide attempt when he was a teenager came from Jules; Anne’s observation that the French lie more readily than the English was taken from a governess character, Mathilde, although she was speaking of the Germans rather than the English; the scene in which Claude, Anne and Muriel compare themselves to different parts of a waterfall originally involved Jules, Jim and Kathe. (In addition, Roché’s journals served as a supplementary source.) Certain images appear in both films: Jim and Claude bicycle behind Catherine and Muriel, respectively, admiring the backs of their necks in secret; Catherine raises her netted veil upon first meeting Jules and Jim, and Anne does the same when introduced to Claude.

The veil scenes illustrate some significant differences between the two films. When Anne lifts up her veil, it happens in a single straightforward shot; when Catherine does it, the ostensibly simple action is captured in four rapid shots, followed by five more showing her now-exposed face from various angles and distances. On a stylistic level, both moments befit their respective films. There’s a playfulness to Jules and Jim, an experimental quality, a sense that anything goes: freeze frames, onscreen text, archival footage from the era in which the movie is set (although some of the events depicted in the archival footage — including World War I and a book burning — are deadly serious). Truffaut may have regarded it as an old man’s film, but it bears clear marks of a young director playing around with his craft. While Two English Girls has its own stylistic touches, including the use of iris shots (meant to evoke early twentieth century films) and several scenes in which characters speak their letters on camera, the feeling of playfulness is almost entirely absent.

Moreover, the emphasis placed on Catherine’s veil scene by these many shots increases the moment’s impact. Claude, seeing Anne’s face clearly for the first time, is “struck by a pleasing and demure nudity,” a simple, modest idea; for Jules and Jim, on the other hand, Catherine is the flesh and blood embodiment of a statue that enchanted them with its tranquil smile. (“Had they ever met such a smile? Never. And if they ever met it? They’d follow it.”) Catherine turns out to be anything but tranquil, certainly, and lives according to her own (sometimes perverse) will; strikingly, she raises her veil again right before jumping into the Seine in retaliation for a misogynistic speech from Jules. Still, it’s interesting that she’s associated with a sculpture while Anne is a sculptor, a creation versus a creator — emblematic, perhaps, of the fact that Jules and Jim is the more idealized of the two films.

Art of all sorts is inextricably tangled up with life for the characters of both Jules and Jim and Two English Girls, Anne and Claude especially. (Claude, like Roché, becomes a collector.) They make art; they live surrounded by art; they meet lovers through art. When Claude breaks his engagement with Muriel, he writes that he’s decided to focus on his work, traveling and writing about painters, which he deems “no life for a wife and children” (though it won’t stop him from having “lady friends”). Later, when he suggests that Anne might become involved with several men, her reply is similar: “I don’t know. I want to work, and work some more. Instead of children, I’ll make statues.”

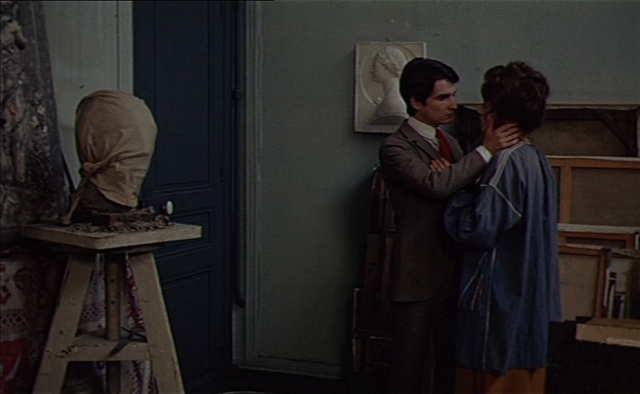

Inevitably, the lines between art and life blur: Anne notes that she was once attracted to a man with a perfectly symmetrical face; Claude, following the end of his engagement to Muriel, decides to get rid of a recently acquired painting that resembles her; when Claude and Anne first acknowledge their romantic feelings for each other in her studio, she feels compelled to cover a bust of Muriel’s head with a piece of fabric, lest it see them. (Even Claude’s mother has something of this mindset. “When your father died, I raised you. I called you ‘my monument.’ I built you, brick by brick,” she tells — or warns — her only child.) More cruelly, upon receiving by mail a profoundly intimate, painful confession from Muriel about a matter of great shame to her, Claude is less interested in her feelings than in its potential literary value, so much so that he wants to publish it anonymously as a pamphlet. He asks Muriel for permission; she refuses, careful not to show him “how much his reaction hurt”; he goes ahead with the project anyway.

According to Gruault, that was exactly what Roché did with the real life Muriel’s confession by including it in the novel Two English Girls, albeit many decades after the fact: “Roché copied her confession in full. It was in the documents that he himself had kept. He had kept the girls’ letters.” Truffaut could relate. In his 1973 film Day for Night, which focuses on the goings-on behind the scenes of a movie, the director character — played by Truffaut — consoles the lead actress during a moment of crisis, then turns her words into dialogue. Asked about it in an interview, he admitted to doing the same thing himself: “That has often happened to me. I realize that there is something cruel about it. This is, in fact, one of my memories of Jules and Jim. Jeanne Moreau had a personal problem. She was upset, she was crying (there were no scenes involving tears in the film) and three days later, I put that into a scene, the one in which she and Oskar Werner are crying together, and I gave her several lines that she had uttered when she was distraught.”

The director frequently mined his own life for material as well, most notably in his five films about the character Antoine Doinel, beginning with 1959’s highly autobiographical The 400 Blows. He contended, however, that the public’s perception of his work was inaccurate: “Although people generally think that the ‘Doinel’ series is autobiographical, whereas the series of adaptations I have made simply attest to my literary predilections, the reality is very different. I have a great propensity to talk about myself, but a very great dislike of doing it directly. For this reason, I feel that I am projecting myself more personally and sincerely through borrowed subjects — Mississippi Mermaid, The Wild Child, Two English Girls — than through the Doinel films.”

Truffaut’s deep personal connection to Two English Girls is evident from the opening credits, which play over images of the novel heavily annotated in his handwriting. (Georges Delerue’s music heard during these credits, ominous and then sad, both sets the tone for the film and helps separate it from Jules and Jim, the main theme of which — also by Delerue — is positively circus-like.) His daughters Laura and Eva appear in the first scene; one of Claude’s briefly seen “lady friends” (somewhat bizarrely) shares her name, Monique de Monferrand, with his aunt. (Only seven years his senior, she was responsible for taking him to the movies when he was a child, sparking his lifelong obsession with cinema.) More significantly still, he chose to narrate the film himself; in Jules and Jim, that role had gone to actor Michel Subor. “Commentary, for me, is a form of confiding — it is like speaking in someone’s ear,” he explained. That said, he wasn’t particularly happy with his own performance. Writing to director Bernard Dubois in 1978, he called his voice “rather unusual” and asserted that “my voice-off narration in Two English Girls was a contributing factor in that film’s failure.” (Facing a box office disaster and harsh remarks from some critics, he pulled the film from theaters after a few weeks and removed fourteen minutes’ worth of material. Shortly before his death in 1984, he had editor Martine Barraqué restore the cut footage and return Two English Girls to its original form.)

At least a few of the alterations that he and Gruault made to Roché’s story also seem to reflect his own life. While some changes are relatively minor, practical — compressing the timeline in places, eliminating less important characters such as Anne and Muriel’s two brothers — others have a much greater impact. The movie kills off Claude’s mother, for instance, while in the book she not only survives until the end but actually speaks the final line. There’s a practical side to this, to be sure, as the death of this intensely possessive woman frees her son to marry if he chooses, and it’s not entirely without precedent because Jim’s mother passes away in the novel Jules and Jim; even so, one can’t help wondering if there’s some connection to the death of Truffaut’s mother, which had occurred in 1968. She was the opposite of Claude’s mother, in a sense, a distant figure with whom the director had a difficult relationship throughout his life. His feelings toward her were further complicated after she passed away, when he discovered in her apartment “press clippings about him, with deletions and markings, which proved that she had been interested in him and not indifferent,” according to his ex-wife, Madeleine Morgenstern. If 1979’s Love on the Run, the final film in the Doinel series, is any indication, he continued to grapple with maternal issues for years.

Killing off Madame Roc is one thing; killing off Anne is quite another. The book gives her a happy marriage, four children and an at least moderately successful artistic career; the film gives her tuberculosis. This, too, has a practical side — it removes another obstacle between Claude and Muriel — yet there’s more to it than that. Truffaut noted that Roché “doesn’t have anyone dying, but it seemed indispensable, to me, in the end.” He felt that “the hero of Two English Girls is a bit like a young Proust who has fallen in love with the Brontë sisters,” and so he and Gruault drew inspiration from the authors’ lives, even putting a paraphrased version of Emily Brontë’s reported last words in Anne’s mouth: “If you wish to call a doctor now, I won’t refuse to see him.” (Additionally, it’s mentioned at one point that Muriel might teach in Brussels, as Charlotte Brontë did, and George Richmond’s portrait of Charlotte can be seen hanging by the Browns’ stairs.) “Of course, it is not her, of the two of them, that one would expect to die — it would have been Muriel,” he said. “In cinema, it is always the idealistic characters that one most readily sacrifices. I wanted to do the opposite.”

Carole Le Berre, in her book François Truffaut at Work, suggests another element at play here: “Is this, in this film of exorcism, a memory of Françoise Dorléac, run down on a road in 1965 [sic]?” Dorléac was the female lead in Truffaut’s 1964 film The Soft Skin, during the shooting of which the two had a short-lived affair. They remained close friends afterwards, and when she was killed in a car accident in June of 1967, Truffaut was devastated. “Françoise, Framboise, death in the summer. I knew it was painful. What is solitude? It is the intolerable,” he wrote a few days after the tragedy. It might seem a stretch to connect Anne’s demise with Dorléac’s, dissimilar as the two deaths were, until one remembers that the actress had a sister of her own: Catherine Deneuve. Truffaut and Deneuve became romantically involved when she starred in his 1969 film Mississippi Mermaid, and their break-up at the end of 1970 so depressed and distressed him that he checked into a clinic and underwent a sleeping cure. (This was a curious case of life imitating art: in Mississippi Mermaid, Jean-Paul Belmondo’s character goes through the same treatment after being left by Deneuve’s.)

It was in the clinic that Truffaut re-read Two English Girls and began to work on the film in earnest. (He first tried to obtain the rights to the novel back in 1967, and Gruault had already presented him with a 552-page screenplay, but he had put it aside temporarily, intimidated by its length. Per Gruault, Truffaut jokingly “claimed he never had the courage to read” it. The two men and assistant director Suzanne Schiffman managed to cut it down by nearly two-thirds.) While any project might have been a welcome distraction, a story about the pains of love was especially appealing to the director just then. “When one is writing, when one is filming, it is satisfying to make characters suffer in your place,” he said.

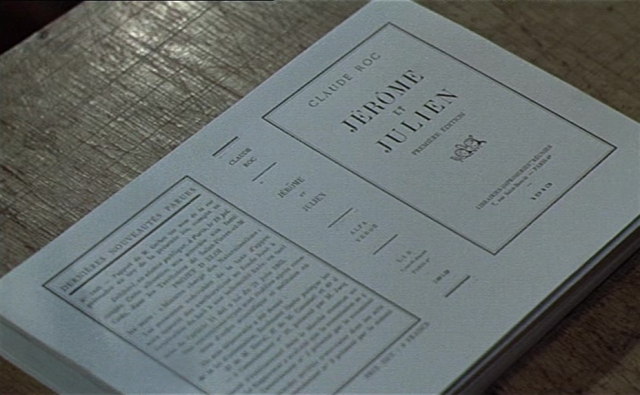

This belief in the therapeutic power of artistic creation shows up in the film itself, in a segment that doesn’t appear in the source novel. After being rejected by Muriel, a depressed Claude copes by writing a book entitled Jérôme and Julien. “This story of a woman who loved two men was a barely disguised account of his experience with the two sisters,” Truffaut says in his narration — autobiography in the guise of fiction. Roché did it, albeit as a much older man; so did Truffaut, through his films. As a matter of fact, the director had employed this idea in his previous film, 1970’s Bed and Board, in which Antoine Doinel begins writing a novel about his life, and he would expand on it in Love on the Run, though it’s treated more lightly in those movies than in Two English Girls. (Jules and Jim also has Jim mention that he’s working on an autobiographical novel about characters named Jacques and Julien.)

By 1971, Jean-Pierre Léaud had played Antoine Doinel in four films, beginning when he was fourteen years old, and was consequently accustomed to serving as Truffaut’s onscreen stand-in (though the character also came to be based on Léaud himself); however, playing Claude posed a significant challenge. “In Two English Girls, the story was terrible in relation to François’s life, and for me it was the same thing. I shouldered everything,” he reflected in 2001. Besides that, Claude was far removed from his own personality and background and from his previous acting experience. In an on-set interview for the television program Pour le cinéma, Truffaut said, “This is a real performance for him. I think that the hardest thing for him is to play someone who was born rich and feels comfortable in life, unlike Antoine Doinel. Antoine Doinel is a shy boy who manages to get by but who belongs to a lower social class. Roché was a tall, thin man, and Léaud has to act as if he was tall, as if he had been born rich, as if he was sporty and in harmony with life.” Oddly enough, Léaud and Roché — as well as the character Claude, judging by the novel — did at least share a birthday, May 28th, sixty-five years apart.

For the roles of the Brown sisters, Truffaut chose Kika Markham and Stacey Tendeter “from among sixty or seventy young English actresses,” according to the Pour le cinéma interview. “I didn’t want starlets,” he explained. “I didn’t want perfect girls with symmetrical faces. I wanted girls from real life.” The two had little to no film experience, but they had worked in television and on the stage, which Gruault considered fitting for the story at hand. “Basically it’s right that Léaud, who is astounding in this film but who isn’t a skilled actor — a true thespian, as they say — should be with two girls superior to him as actresses, who performed on stage — who still do, Shakespeare and so on,” he said in a DVD commentary recorded in 2000. “That sums up the situation.”

Claude may be more worldly than the sisters, but in many ways, Anne and Muriel prove to be more vital. “I always have female characters that are stronger than my male characters,” Truffaut said. Even the girls’ French seems stronger than Claude’s rarely heard English, in this film where language, letters and literature are ubiquitous (typical of Truffaut’s work, though it’s especially prominent here). Whether in spite or because of their sheltered upbringing — Anne, for example, remarks that she didn’t know the meaning of the word “virgin” until she read Émile Zola’s Germinal — the Browns are highly curious and often surprisingly open-minded, forever engaging in discussions with Claude about books, moral issues and the world beyond their ken. “To choose, one must know both choices. How can I choose between virtue and vice? I only know virtue!” Muriel says. Unlike their mother, who worries about the opinions of others and disapproves of her daughters’ “modern ideas” that Claude helps foster, Anne and Muriel tend to act according to their own beliefs, thoughts, feelings and consciences — though that leads them down very different paths.

Muriel is both the more traditional and the more forceful personality, to the degree that Anne — despite being the elder sister by two years — has grown up in her shadow. (In the novel and in an earlier draft of the script, Anne is the younger sister; the birth order may well have been switched because Markham was nearly a decade older than Tendeter.) High-minded and religious, she views her relationship with Claude in absolute terms. “I want Claude completely or not at all,” she declares. (At one point, she even takes communion for him in a church, though she admits that she doesn’t know what she means by that.) Truffaut described her as “a puritan in love” and said that he was pleased with the way “she contradicts herself from one scene to the next, and sometimes within a single scene” as she struggles with her feelings and her situation. Her struggle is so intense that, combined with her temperamental nature, it leads to physical suffering: fainting, fevers, nausea.

This physical dimension was of great importance to Truffaut, as he explained to the magazine L’Avant-Scène Cinéma: “Like nearly every story about feelings, Two English Girls deals with loves impeded and thwarted, but the obstacles — even if the most important among them is made concrete by the attitude of an over-possessive mother — are moral, interior, I would even say mental. I felt the need to go further in the depiction of amorous feelings, a little further than one usually goes. There exists sometimes in love a true violence of feelings, and it’s that I wanted to film; I’m not speaking only of embraces, which I’ve tried to treat with objectivity and crudeness, without music, but also avowals, confessions, ruptures that can drive the characters to vomiting or fainting. To summarize this endeavor in a sentence, I have tried to make not a film about physical love but a physical film about love.” Physical love is a key theme nonetheless, and Claude’s differing experiences with the two sisters emphasize their dissimilarities. With Anne, consummation is a gradual, gentle process, spread out over several nights, and Truffaut cuts away discreetly; with Muriel, even though it’s delayed for years, the act itself seems sudden, almost violent when it does occur, and a good bit more is shown, in keeping with the physical quality of Muriel’s love.

Anne, more temperate than her sister, doesn’t suffer from love to nearly the same degree. Lacking Muriel’s absolutism, she’s willing to act on her desires, to experiment with love. In fact, it seems that she may be afraid of the absolute, judging by what she tells Claude once they’ve become a couple: “I’m too happy. I should love others. I’ll let you do the same. Love me while you can.” Maybe it’s practicality rather than fear, combined with a knowledge of Claude’s inability to commit to one woman (a bit like Jim’s rather-too-tolerant longtime girlfriend, Gilberte); maybe it’s her lingering inferiority complex from growing up with Muriel. Her character only starts to emerge clearly when she gets away from her sister, setting herself up in a studio in Paris where she can work on her sculptures and lead a free life, even becoming involved with multiple men simultaneously if she so desires.

Although Anne breaks conventions, there’s a kind of modesty or honesty about her behavior, her quest to experience and understand love. It never comes across as rebellion for rebellion’s sake, or for spite, as the impulsive Catherine’s actions sometimes do; for example, after Jules’s mother offends her on the eve of their wedding and Jules fails to defend her, Catherine goes off with an old lover for several hours in order to punish her soon-to-be husband. “She jumped into men’s arms like she’d jumped into the river,” the narrator of Jules and Jim says. In more ways than one, it’s difficult for the enamored men around her to get a handle on her — Jim describes her as “a vision for all, perhaps not meant for any man alone,” Jules calls her “a force of nature that manifests in cataclysms,” and the narrator says, “Catherine meant different things to each and couldn’t please them all, but too bad” — and the same may be true for the viewer. A scene midway through the film has her open up to Jim about her marriage to Jules, offering a rare glimpse at her deepest, most personal thoughts and feelings, yet she gives him a word of caution at the end: “I don’t want to be understood.” In contrast, the Brown sisters’ inner lives — Muriel’s, especially — are very much on display throughout Two English Girls as they constantly analyze and talk about their emotions and their ideas about love. “They comment on them for each other, between themselves, without respite,” said Truffaut, who also remarked, “I hope that I haven’t depicted Two English Girls from a masculine perspective.” As such, they seem less enigmatic than Catherine, and better developed than Claude as well.

Truffaut acknowledged that Claude — like Jim — is something of a vague figure, no doubt as a result of being based on Roché himself, and explained that he encouraged Léaud to maintain a neutral expression when the character is listening or observing “so that no one could impute discernible emotions to him at those moments.” Moreover, despite the fact that Claude is supposed to be comfortable in life, confident in his wealth and social position, there’s a certain passivity to him, a certain diffidence, common in Truffaut’s heroes. At the start of the film, he peeks into the room where Anne is sitting but quickly backs away, waiting for his mother to enter with him. “You’re not a child. Introduce yourself,” she says. In the next scene, Anne tells him that he no longer needs the cane he’s using after a leg injury and orders him to hand it over; later, when he’s reunited with Muriel after four years apart, he’s so frightened and intimidated by her purity that he has to walk away, only to have her boldly approach and kiss him. It’s worth noting that none of these examples of Claude’s hesitancy appear in the book.

Another scene, derived from Roché’s novel but shifted in setting from a cable car to the outdoors, makes Claude’s passivity literal, neatly symbolizing and foreshadowing his complicated relationship with Anne and Muriel. Caught in a rainstorm, the three young people and the girls’ mother take shelter at the mouth of a cave. In order to pass the time until the weather improves, Mrs. Brown suggests that they play a game called citron pressé (or “squeezed lemon”), in which she sits between her two daughters as they rock her from side to side, pressing against her with their backs. She soon asks Claude to take her place, and Anne and Muriel push him to and fro, first toward one sister and then toward the other.

Make no mistake: Claude is hardly a helpless victim in this story, unless one considers him a victim of forces beyond his control. As the incident with Muriel’s confession illustrates, he can be downright callous; Truffaut described him as someone who “always looks on his love affairs with an aesthetic eye, even when he is leaving women gasping for breath, broken,” and it’s said that he breaks many hearts without ever feeling the pain himself — until Muriel rejects him. She and her sister are special to him, set apart from all of the other women who pass in and out of his life. Maybe it’s because they’re different from the rest; maybe it’s because he’s still largely innocent himself when he meets them. He can answer their questions about brothels (though not without embarrassment) and talk about his adolescent suicide attempt, but he still has enough of the child about him to enjoy such juvenile amusements as spinning around and posing like a statue.

Citron pressé, however, is not as innocent as it looks. (It’s telling that Truffaut said that his intent in making Two English Girls was “to squeeze love dry like a lemon.”) “Emotion swelled in Claude, a pawn in an unknown game,” the narrator comments. “Pressed between the sisters, breathing their scent. He’d spent weeks with them, yet he’d barely touched their hands, and now their supple backs leaned into him with all their strength. It felt too intimate.” This time, Claude’s expression isn’t neutral; instead, surprise, pleasure and uncertainty flicker across his face. In spite of Anne’s efforts to bring about a romance between Claude and Muriel, his relationship with the Browns is essentially platonic up until this point. He calls them his sisters; they call him their brother. Physical contact of this sort, unprecedented and unacceptable in any other context, is literally smiled upon by Mrs. Brown, just as she and several neighbors laugh approvingly in an earlier scene when Claude must kiss Anne on the cheek in order to to “pay a forfeit” during charades. The charade kiss isn’t such a lighthearted matter to the three young people. Before proceeding, Claude turns back to see Muriel’s reaction; she averts her eyes, hidden behind dark glasses while they recover from a strain, but she can’t entirely conceal a touch of unhappiness — of jealousy, even. Already, their triangular arrangement is posing problems, however minor.

Both Mrs. Brown and Madame Roc view the trio as a kind of safeguard. The latter, confronted with the possibility that her son may be falling in love with Muriel, rejects it firmly. “That’s out of the question. He likes both of them,” she says. Later, she approves of his promiscuous lifestyle for the same reason: better for him to have casual, meaningless relationships with multiple women than a committed relationship with one, which would threaten her own hold on him. Mrs. Brown, meanwhile, is concerned about the rumors that might arise if Claude appears to favor one sister over the other, considering that he’s living in the Browns’ house; she’s relieved, for instance, that people mistakenly believe Anne was present during a late-night conversation between Claude and Muriel. “A young lady must not cause gossip. Her reputation is at stake,” she tells him before sending him away to stay with their neighbor instead — and unintentionally galvanizing his love for Muriel by suggesting that she might have unacknowledged feelings for him.

Thus, Mrs. Brown helps achieve by accident what Anne has been working diligently to accomplish. Again and again, the characters make plans for themselves and for other people — Claude’s father even took his pregnant wife to the Louvre so that their unborn son would love art — yet they rarely turn out as intended. Claude desires the sisters, and they him, but in the end they want different things, especially as they learn and change over time. To a degree, they’re blinded by their ideals, by the images they’ve created of one another. Claude hears about Muriel from an admiring Anne and sees her in a childhood photo long before he actually meets her; when he does, she has a bandage around her eyes, obscuring her face far more than Anne’s veil obscured hers and adding an air of mystery. Although he soon develops a genuine, personal relationship with her, the narrator offers a revealing insight when Claude is exiled to the neighbor’s house: “He dreams too much of Muriel to regret losing her company.” Muriel, meanwhile, obsesses over Claude even as she comes to realize that their views and lifestyles are incompatible, that he’s no longer what she once knew or thought him to be — something that she accepts better than he does, at last. Characteristically, Anne is more willing to compromise than her sister is, but that can be difficult, painful. Once she and Claude have been on-and-off lovers for some time, the narrator says, “Her instinct was to have one man in her life, but Anne knew if it wasn’t Claude, she’d fight that instinct” rather than give him up completely. She admits, too, that she was sometimes jealous of Muriel’s relationship with Claude, despite the fact that she was the one responsible for bringing them together — so much did she consider herself her sister’s inferior, though one early scene shows Muriel privately resolving not to be jealous of Anne.

Claude experiences jealousy as well. He encourages Anne to take other lovers, proclaiming that “curiosity is sacred,” yet he’s hurt in spite of himself when she actually does become involved with another man. (The narrator again: “It bothered both men, but not Anne.”) Human relations — love, in particular — are a messy business, complicated by physicality and feelings, regardless of the principles that the characters try to uphold and the ideals to which they aspire. This is reflected visually in the film, which juxtaposes period settings and costumes with the natural world, untamed and unpredictable, to which the central love triangle is closely connected. In the early, platonic days, Claude and the sisters spend much of their time outdoors; he and Anne consummate their relationship in a rustic cabin on an island in a lake; and he tells Muriel, “You’re of the earth. I like that.” Of course, the fact that there are three people involved in this situation increases the messiness, even when only two of them are present — or alive. “Between them was a dead woman whose name he didn’t utter,” the narrator says of Claude and Muriel after Anne’s passing.

Compared to that of Two English Girls, the ending of Jules and Jim is relatively neat, though grim: Catherine destroys herself and Jim in one fell swoop, putting a definitive end to the love triangle and leaving Jules with his daughter and a strange sense of relief. The cruder Two English Girls finds Anne dead of a disease beyond her control and Claude and Muriel alive but unable to be together after all that they’ve been through, Claude feeling certitude for the first time just when Muriel decides to bury their love and move on with her life. “I can live without you, like one lives without eyes or legs,” she says the morning after their first and last sexual encounter, bringing in the physical element again. She marries another man and has a child; Claude is left alone with his memories and regrets. The final scene, set fifteen years after the previous one, and after the international devastation of World War I, shows a middle-aged Claude touring the grounds at the Musée Rodin — a complement to a scene at the beginning of the film, in which he introduces Anne to Auguste Rodin’s work. Noticing a group of British schoolgirls there, he wonders if one might be Muriel’s daughter, but he doesn’t ask because he sees no point in it. As Carole Le Berre points out, “She is her daughter in reality in Roché’s novel, but only virtually in Truffaut, whose vision is more cruel.” The camera pans around Rodin’s The Kiss, a depiction of love not only physical and passionate but unchanging, ageless. Claude then studies his reflection in the window of a car and wonders, “What’s wrong with me? I look old today.” Art — moving, inspiring or even healing in other contexts — becomes a mockery.

“I think I like the image of life better than life itself, because I don’t think real life is as satisfying as a film,” Truffaut said on a 1969 episode of the television program L’Invité du dimanche. This theme plays a major part in Day for Night, naturally enough, but the essential idea is also at the heart of Two English Girls, with its focus on both art and the disappointments, heartaches and confusion of love in reality. “My life is made of pieces that do not fit,” Muriel laments in the midst of her suffering. It’s also a film about the loss of innocence, made by a director who had gained painful experience of his own in the ten years since he shot its sister film, Jules and Jim. The two — the first “a hymn to life,” the second “a film about grief,” as Truffaut described them — are as similar and as different as Anne and Muriel themselves.

Sources

De Baecque, Antoine and Serge Toubiana. Truffaut: A Biography. Trans. Catherine Temerson. Knopf, 1999.

Gaskell, Elizabeth. The Life of Charlotte Brontë. Penguin, 1997.

Gruault, Jean and Serge Toubiana. Audio Commentary. Les Deux Anglaises et le Continent. MK2, 2004.

Le Berre, Carole. François Truffaut at Work. Trans. Bill Krohn. Phaidon, 2005.

Peron, Didier, and Antoine de Baecque. “Leaud, retour à Doinel.” Libération 31 August 2001. http://next.liberation.fr/cinema/2001/08/31/leaud-retour-a-doinel_375593

Roché, Henri-Pierre. Jules et Jim. Trans. Patrick Evans. Penguin, 2011.

Roché, Henri-Pierre. Two English Girls and the Continent. Trans. Walter Bruno. Cambridge Book Review Press, 2004.

Truffaut, François. Correspondence 1945-1984. Trans. Gilbert Adair. Cooper Square, 2000.

Truffaut, François. Interview. Bibliothèque de poche. 12 October 1966.

Truffaut, François. Interview. L’Invité du dimanche. 26 October 1969.

Truffaut, François. Interview. Pour le cinéma. 1971.

Truffaut, François. “Les Deux Anglaises et le Continent.” L’Avant-Scène Cinéma Jan. 1972: 13-64.

Truffaut, François. “Mes deux anglaises, mon onzième film.” L’Avant-Scène Cinéma Jan. 1972: 10-11.

Truffaut on Cinema. Ed. Anne Gillain. Trans. Alistair Fox. Indiana University, 2017.