I’m not sure when I first encountered the name “Gérard Philipe,” though it must have been quite a while ago. As a fan of classic French films, I suppose it was inevitable that I would do so at some point, yet there was always an odd vagueness about it, a lack of substance — as if the actor to whom it belonged never managed to take shape and instead remained little or nothing more than a name to me. For one reason or another, I almost never ran across him in anything, despite the fact that he was a big star in the post-World War II, pre-New Wave era. (His screen career, which began in 1944, came to an abrupt and tragic end when he died of liver cancer in November 1959, just over a week shy of his 37th birthday.) He did appear in La ronde (1950, directed by Max Ophüls), which I watched several years back, but that was very much an ensemble piece and I have no particular recollection of his involvement, or of much of anything beyond the always enjoyable Anton Walbrook as the master of ceremonies. Some time after that, I finally saw Philipe in a leading role as the mysterious figure at the center of the 1949 Yves Allégret-directed film Such a Pretty Little Beach (Une si jolie petite plage). I was impressed by his performance and his screen presence and told myself that I should seek out more of his work, yet a few more years have passed since then and somehow that still hasn’t happened. As such, he struck me as an ideal candidate for The Third Marathon Stars Blogathon. The rules are fairly simple: pick an actor whom you’ve seen in no more than three films and watch at least five new-to-you films featuring that person. I decided to watch my selections in chronological order in hopes of gaining a better sense of Philipe’s development as an actor and as a movie star, and I also made a point of choosing works by different directors.

Continue reading “Gérard Philipe in Five Films”Hiding in Plain Sight: The Bad Sleep Well (1960)

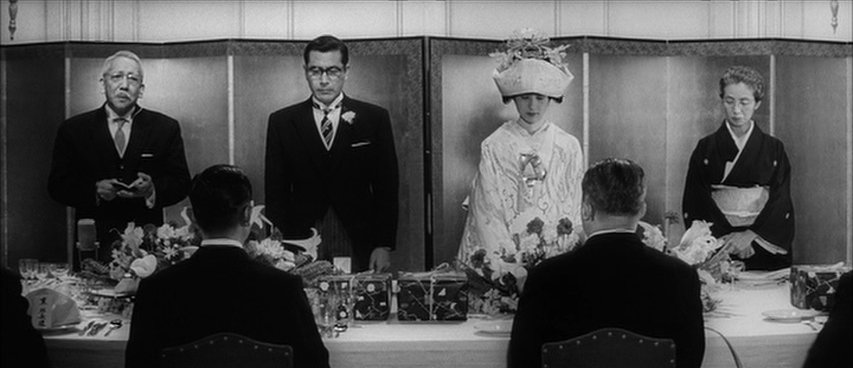

“Hell of a wedding.”

“Truly bizarre. Best one-act I’ve ever seen.”

“One-act? This is just the prelude.”

Akira Kurosawa’s 1960 film The Bad Sleep Well (悪い奴ほどよく眠る or Warui yatsu hodo yoku nemuru) opens with a lengthy scene depicting a most unusual wedding reception, not least of all because the newlyweds often come across as a kind of afterthought — a pair of quiet, unobtrusive figures largely overshadowed by the dramatic events unfolding around them. The bride, Yoshiko Iwabuchi (Kyôko Kagawa), is the daughter of a vice president (Masayuki Mori) at the Public Corporation for Land Development; the groom, Kôichi Nishi (Toshirô Mifune), formerly the owner of a small used car dealership, became his new father-in-law’s secretary upon the couple’s engagement. For five years, a cloud of suspicion has hung over executives at Public Corp. (including Vice President Iwabuchi) and at Dairyu Construction due to their alleged involvement in a kickback scheme on a government project. Now, at last, the situation appears to be coming to a head, just in time for the reception. Wada (Kamatari Fujiwara), Public Corp.’s assistant chief of contracts, is arrested shortly before it begins; Dairyu’s president, Hatano (Someshô Matsumoto), is asked to make a congratulatory speech to the young couple and uses the opportunity to declare that he has no personal ties to Public Corp.; and, most sensationally, a massive and mysterious cake arrives, modeled after the government ministry building where an assistant named Furuya jumped to his death five years earlier — complete with a rose marking the exact window where it happened.

Continue reading “Hiding in Plain Sight: The Bad Sleep Well (1960)”Like a Complete Unknown: Girl with a Suitcase (1961)

Over five minutes elapse before the name of the 1961 Valerio Zurlini-directed film La ragazza con la valigia, or Girl with a Suitcase, appears onscreen, superimposed on a shot of the titular piece of luggage sitting on the floor of a garage — symbolic of the fact that, unbeknownst to her, its owner (Claudia Cardinale) has just been unceremoniously abandoned by a young man (Corrado Pani) in whom she’s placed her trust. At this point she’s already been introduced to the viewer, and in rather memorable fashion at that. The opening scene finds her riding in the passenger seat of a stylish convertible, but any glamour that this might attach to her is immediately undercut by a distinctly unglamorous act: she has to get out of the car in order to urinate in the bushes along the side of the road. In spite of the quasi-intimate nature of this debut (the act itself takes place off-camera), little of substance has been revealed about her by the time the words La ragazza con la valigia pop up, words that suggest both transience and anonymity. (The English title takes this a step further by dropping the definite articles of the Italian original.) Although she won’t remain unknown for long, the impression that Aida Zepponi just may be on the verge of slipping into total obscurity never entirely goes away.

Continue reading “Like a Complete Unknown: Girl with a Suitcase (1961)”The Avengers: “The Hour That Never Was” (1965)

I was a teenager when I first discovered The Avengers in reruns on BBC America. As I recall, it aired in the late afternoon, shortly after I came home from school, and it wasn’t long before the series — which initially ran from 1961 to 1969 on the British network ITV — became part of my weekday routine. Ordinarily, I’m not sure that I would have had much interest in a show about secret agents, but I could tell from the start that this particular show was something unique, something special. Menacing wheelchair-bound nannies, men repeatedly getting hit by cars with no ill effects, mind-swapping machines, training schools for proper English gentlemen, nods to the Adam West Batman, quaint villages where murder could be overlooked for the right price — I never knew what to expect, but I did know that it would be fun and entertaining and probably more than a little quirky. In the midst of all that, there was always a mystery to be solved, and it was sure to be solved with wit and style (as well as a fight or two) by the dynamic duo of John Steed (Patrick Macnee) and Emma Peel (Diana Rigg). Emma would eventually be replaced by Tara King (played by Linda Thorson) following Rigg’s departure from the series, and although I didn’t dislike Tara and enjoyed quite a number of the episodes that featured her, nothing could match that Steed and Mrs. Peel pairing.

From what I remember, BBC America exclusively ran the color episodes of The Avengers; at any rate, those were the only ones I ever saw there. It wasn’t until several years later that I encountered the black-and-white portion of the series, including the early episodes that teamed Steed with Honor Blackman’s Cathy Gale and, better yet, a slew of new-to-me Emma Peel adventures. There were a lot of gems among them, and one of my favorites is an episode directed by Gerry O’Hara and written by Roger Marshall that premiered in November 1965: “The Hour That Never Was.”

Continue reading “The Avengers: “The Hour That Never Was” (1965)”Seen and Unseen: The Fallen Idol (1948)

The 1948 movie The Fallen Idol, directed by Carol Reed, is a film of watching and being watched, of seeing and not seeing, of incomplete knowledge and lies and misunderstanding. It begins with the very first shot: a close-up on a young boy (Bobby Henrey), his face framed by a balustrade, as he gazes down at the brisk comings and goings of the numerous adults far below him, on the ground floor of his house. His house, as it happens, is an embassy in London, and most or possibly all of this bustle is due to the fact the ambassador (Gerard Heinz) — his father — is about to depart on a brief trip in order to bring the boy’s mother home from an eight-month-long hospital stay. Servants race to bring the ambassador’s bags out to his car; last-minute changes are made to the travel arrangements; preparations for the woman’s homecoming are discussed. Even when the boy, Phillipe (often called Phile, pronounced with a short i), descends the stairs partway in order to get a closer view, nobody appears to take the slightest notice of him save for one man: Baines (Ralph Richardson), the butler. Despite being occupied himself, Baines makes a point of acknowledging and entertaining the little onlooker. A playful hop when he empties an ashtray into the fireplace, a wink — small things, maybe, but enough to make Phile smile and to suggest the warm friendship between the two. It’s Baines, too, who says, “Master Phillipe, sir,” as the ambassador is leaving, as if to remind him to bid farewell to his son. One gets the sense that he might well have forgotten otherwise.

Continue reading “Seen and Unseen: The Fallen Idol (1948)”The Adventures of Pete & Pete: “Grounded for Life” (1994)

At the risk of overgeneralizing, it seems reasonably safe to say that any television series that features a metal plate in a woman’s head and a preteen boy’s tattoo in its opening credits, presenting them as equals with the rest of the show’s main characters, is bound to be at least a tad offbeat — and that’s not even accounting for the fact that the two of those other main characters are brothers with the same first name.

Welcome to the weird and wonderful world of The Adventures of Pete & Pete.

Continue reading “The Adventures of Pete & Pete: “Grounded for Life” (1994)”Ladies, Be Careful of Your Sleeves

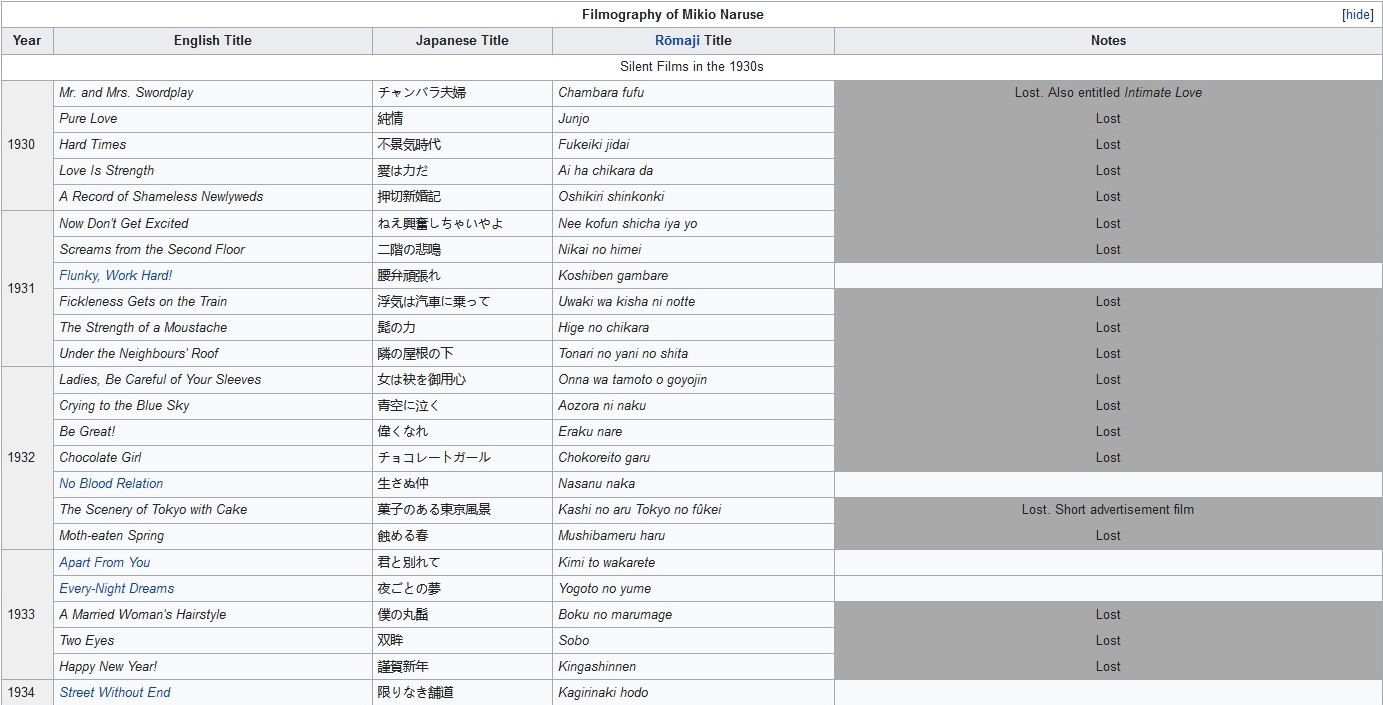

In the midst of writing a post on two of Ozu’s silent films, I looked up Mikio Naruse’s filmography on Wikipedia and was reminded that his silents, in particular, are a goldmine of delightful and intriguing titles (at least in English). What a shame that practically all of them are lost, though I do have to wonder if Fickleness Gets on the Train or The Scenery of Tokyo with Cake could ever live up to my expectations.

Le Cinéma de Papa

If the cast list on IMDb is to be believed, Marcello Pagliero’s 1950 film Un homme marche dans la ville features an appearance by Pierre Léaud, the film’s assistant director and the father of Jean-Pierre Léaud, as “l’ordonnateur.” While the term has several possible meanings, the only one that appears to fit here is “the undertaker,” which would presumably make Léaud père the small man with the mustache and glasses in the scene linked above (starting around the 1:11:45 mark). Perhaps it’s just a kind of confirmation bias, but some of those mannerisms do look familiar…

EDIT: The video has been removed from YouTube.

The Outstretched Hand

For Satyajit Ray on his 100th birthday, with love and spoilers

There’s a subtle yet particularly cruel visual touch at the end of Satyajit Ray’s short feature The Coward (Kapurush), an added sting in an already cruel scenario. A man sits on a bench at a train station for hours, hoping against hope that his now-married ex-girlfriend, encountered by chance years after he disappointed her when she needed him most, will leave her husband and run away with him. Darkness falls; he nods off. Awoken by the whistle of a train, he’s startled and then delighted to see the woman standing beside him — until he discovers that she simply wants to retrieve the sleeping pills that he had borrowed while staying at her house. “Let me have them, darling,” she says. That “darling,” whether sincere or sardonic, is a devastating touch in its own right, as is the way she vanishes into the blackness of the night when she walks away from him a moment later, her pills recovered. Any viewer is able and apt to appreciate these details, but it takes a familiarity with certain other Ray works to grasp the full significance of a brief shot that falls between them: a close-up of the woman’s extended hand as she waits for the man to turn over the bottle.

Father’s Day: The Thursday (1964)

“Am I young for a father?” Dino Versini (Walter Chiari) asks his girlfriend, Elsa (Michèle Mercier), in the opening scene of Dino Risi’s 1964 film The Thursday (originally Il giovedì). Dino is forty and looks it, so the inquiry seems more than a little silly. Is it simple vanity that compels him to pose this question, a barely veiled attempt to elicit a compliment on his appearance, or does it spring from a deeper insecurity? It’s just possible, also, that at least some part of him genuinely regards himself as someone too youthful to be the parent of an eight-year-old-boy. Today, for the first time since his marriage broke up five years ago, he’s going to spend time with his son, Robertino (Roberto Ciccolini). Although he may not realize it yet, their reunion will force him to confront both his image of himself and the image he tries to project to the world — whatever difference there may be between them.